Last week I went to Melrose with the other USAC students and we visited the famed Melrose Abbey. The Abbey was founded in 1136 and was attacked multiple times during the stormy history of Scotland vs. England. It fell into ruin and disrepair after the Protestant Reformation when the monks were ordered to disband and abandoned the site. Alexander II is the only Scottish king to be buried at the abbey, although Robert the Bruce’s heart is also located there (the rest of him being interred at Dumferline Abbey). Only after returning to St. Andrews did I find out that Melrose Abbey is also the legendary resting place of the wizard Michael Scot.

Michael Scot was a mathmetician and scholar from the Scottish borders 1175 – 1232. He worked for the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, turned down an archbishopric in Ireland twice, and translated Aristotle from Greek into Latin. Meanwhile, back at home, he had a reputation as a wizard and legend has his servants fetching exotic foods from around the globe, building a bridge over the river Tweed, and eventually becoming so annoying that he set them to the impossible task of building a ladder to the moon made out of sand, which they are still attempting to complete to this day. He got his powers from eating and cooking the middle section of a snake that attacked him on the road–much along the same lines at the Irish story of the Salmon of Wisdom. He is associated with Aikon (Oakwood) tower near Selkirk and is reportedly buried at Melrose along with his books.

In John Stoddard’s Lectures (vol. 9) there is a photograph of Michael Scot’s tomb at Melrose:

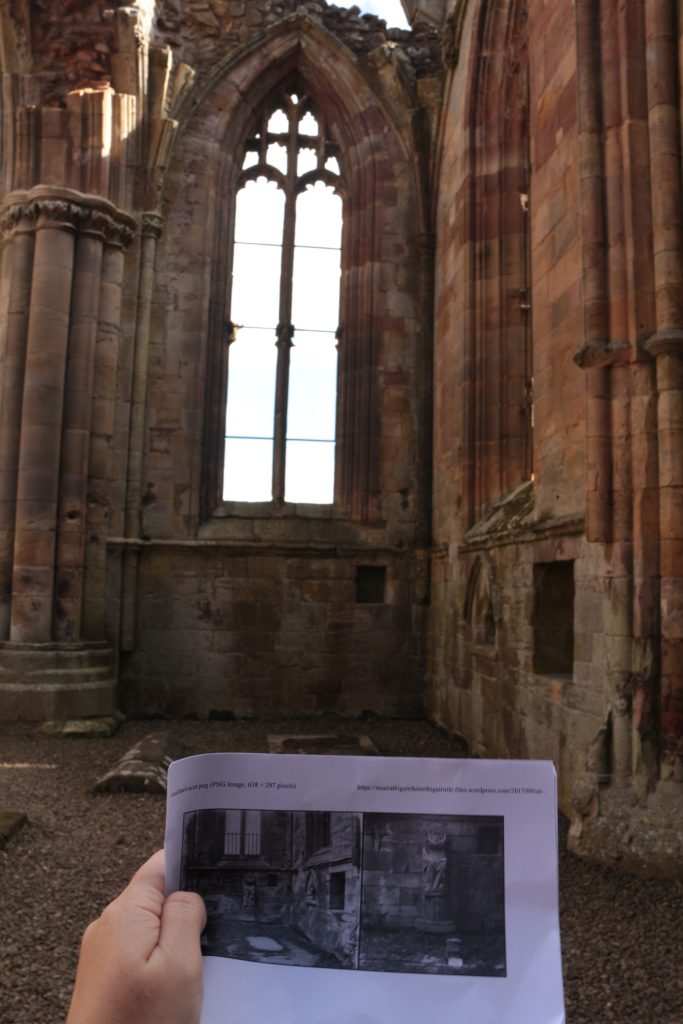

I saw no such thing while I was there and so the following week I planned a follow-up trip of my own to investigate the matter for myself. Photograph in hand, I took the train to the borders and set up figuring out where the tomb was, and how I’d missed it the first time.

Finding the tomb turned out not to be a problem, although the statue was gone.

I knew that the abbey had a museum attached so I went to see if the statue had been relocated there. It was not. I was on my way to find the lady who sold me my ticket to see if maybe there were more Melrose statues in other museums when I pulled the picture out of my pocket and realized that it strongly resembled something I HAD seen in the museum. I pulled the photo up on my camer and sure enough, they matched.

It was not, in fact, part of a statue, but was actually a boss; the carved central part of a boss.

Well, I had my head, but that left the body. Standing in the middle of the abbey I realized I had seen that too, but I hadn’t taken a photo. So I headed back to the museum and sure enough:

I’d had my doubts about the head, but this was definitely the body from the photo in Stoddard’s book. So what happened? The wall above the tomb shows no signs of a statue ever having been there. Did the 19th century abbey curators think that putting a disembodied head with a headless body above the tomb make it more sensational to visitors? Did they have some reason for picking that particular tomb to declare as Michael Scot’s or did they just want to be able to point to one to set wild Walter Scott fans at ease? What happend to the pillar underneath the statue? And what’s going on with this photo, clearly seperate from the Stoddard one, that identifies the grave next to it as belonging to Lord Evers?

We may never know the answer, unless I find the time to dig up obscure museum records or talk to someone involved in moving the ‘statue’ from the abbey to the museum. But at least the riddle of why something photographed in 1898 is no longer extant in the abbey today has been solved, and those who hunt for the grave of Michael Scot can rest assured that it is still a mystery waiting to be unravelled.

One Reply to “The Wizard’s Grave”

Comments are closed.